Enslaved Lives in the Shirley Household

Beginnings of the British Slave Trade

The British slave trade was born out of a desire to out-trade and out-earn other European countries like Portugal and Spain. Like these other countries, Britain quickly became dependent on enslaved labor despite its claim that it was an enlightened, civilized nation. The horrors of the transatlantic slave trade beg to differ. So would those who suffered through them, and so would their ancestors born into an unjust and cruel institution.

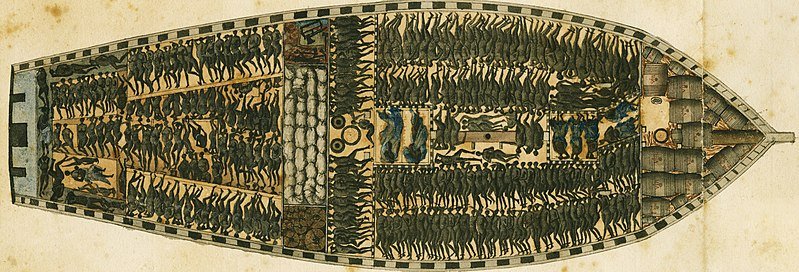

“Slave Deck of the Ship the Séraphique Marie of Nantes…” 1770. René Lhermitte, France. Rotated detail.

European Competition

Europe in the 1500s was fractured. Shifting alliances and war made the positions of kings and queens more and more fragile, and it became necessary for royals to sponsor exploratory ventures that sought new wealth and land to conquer. Spain had been the first nation to lay claim on land in the “New World,” but it was quickly followed by Portugal, England, and France. It was common practice from the outset of European exploration to enslave indigenous peoples, and Africans had also been captured, enslaved, and brought to North America. However, that changed when Spain declared indigenous people to be citizens of the empire. Instead of enslaving them, the goal became conversions to Christianity and assimilation into Spanish culture. Africans were not included under this ruling.

“Franciscus Monteio Lucatanae provinciae praeficictur,” Unknown artist, 1595. Detail. Woodcut engraving showing indigenous people and Spanish colonizers first meeting, then fighting.

Portugal was the first to begin trading in human lives en masse. In 1619, a Portuguese ship sailing to North America was captured by English pirates and taken into port at Jamestown, Virginia. This was the first group of enslaved Africans sold in North America as part of the transatlantic slave trade. While Portuguese sailors trapped and transported the slaves, they were sold in a British colony, under British law. By this time almost all of Europe was either an active participant or complicit in the slave trade. Art, music, and literature from the time reflect this.

Pictured below is French artist Nicolas de Largilliere’s Portrait of a Woman and an Enslaved Servant, completed in 1696. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, where the painting is housed, compares the symbolism of the enslaved boy’s position in the painting to that of dogs in other works – a sign of loyalty to the “master.” The pet names often given to enslaved people such as“Cato,” “Caesar,” or “Venus” erased their original names and symbolized the absolute paternalism of their enslavers. In the portrait below, the enslaved boy wears a collar much like a pet, and he holds a dog to reinforce the comparison.

Portrait of a Woman and an Enslaved Servant, Nicolas de Largilliere, 1696. France. Image courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Quest for Empire

For Great Britain, participating in the trade of enslaved Africans was a stepping stone on the path to empire. By the 1660s, Britain discovered just how profitable North American plantation farming and the resultant trade in humans could be, and the institution became incredibly popular among wealthy families. The British slave trade grew from there, and by 1698, European trade in Africa was opened to all countries. The Royal African Company, as it became known, got its start. The group aimed to monopolize the use of various ports throughout Africa so that only English ships could come in and out.

There are very few African accounts of the voyage to North America. All of them agree that it was inhumanely crowded, far too hot, and sickness abounded below the decks. Olaudah Equiano, a formerly enslaved man who eventually wrote a memoir of his journey, described it vividly. “The closeness of the place, and the heat of the climate, added to the number in the ship, which was so crowded that each had scarcely room to turn himself, almost suffocated us.” Equiano goes on to describe the way many captives would throw themselves into the ocean because they would rather die than live in such misery. While some in Britain protested these vile conditions, the profitability of the slave trade drowned out all objections. Slave ships grew larger and more densely packed as the trade continued. Only the Portuguese had legal requirements on their ships for space and airflow. But these were largely ignored.

This page is but a brief overview of the history and horrors of the British slave trade. For more information and further reading, visit the Learn More section of the exhibit.

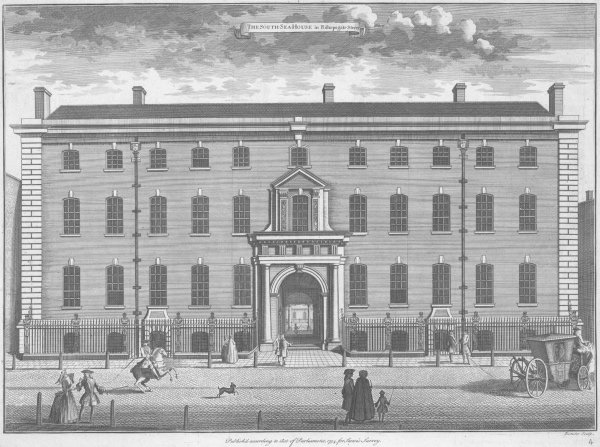

At left: The London headquarters of the South Sea Company, a joint-stock trade organization that was given exclusive rights to trade Africans with the Spanish and Portuguese in 1711. When the business collapsed in 1720, the aftermath led to an economic crisis in Britain. 26 year old William Shirley was one of those who lost the fortune he had inherited from his father in the collapse. His subsequent financial hardships eventually led him to seek a career in America.

“Olaudah Equiano (Gustavus Vassa),” Daniel Orne, 1 March 1789. This engraving was the frontispiece for Equiano’s autobiography, titled The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano.

While the slave trade involved many European nations, each one was seeking to dominate transatlantic trade at the same time. There was tension between the desire to build one’s navy and amass wealth, and maintain good trade relations with other countries, as well. Colonies sprung up left and right in North America and the Caribbean, trying to serve as a foothold on this “new” land with new resources.

This growth came at the cost of unimaginable numbers of human lives. By the 1740s, when William Shirley was Royal Governor of Massachusetts, roughly 55,000 Africans were captured and forced into slavery every year. Between 5,000 and 10,000 of those people are recorded to have died while enduring the middle passage each year, but this number is likely extremely low. The records of slave ship voyages are often incomplete, and we know that in at least a few cases, such as the Dutch ship Zong, white captains killed their human cargo to collect insurance payments. This says nothing of the cost to Native American societies, which were devastated by war and European diseases introduced upon settlement. Some Indigenous tribes lost as many as 90% of their populations.