Enslaved Lives in the Shirley Household

< Back to Enslavement in New England

Duties and Demands: The Many Tasks of Enslaved People

Enslaved people were responsible for the operations of white households in many ways. They cooked, cleaned, gardened, nursed and cared for children, performed trades, cared for animals, and much more. In some ways, this was like the roles of enslaved people in other areas of the English colonies. But there were also key differences. The distinction between what is called “skilled” and “unskilled” labor is also important. Who is considered skilled, and why?

“Sketch of African-American Women Washing Clothes,” Unknown Artist, 1864. Image courtesy Biblioteca Ambrosiana.

Commonalities Across Regions

Mortar and Pestle, c. 19th century. The Shirley-Eustis House Association Collections, 2014WAT.161a-b. Image courtesy the author.

Laundry was another essential labor of people who were enslaved, women especially. Bathing was much less common in the eighteenth century than it is today, and in fact very controversial. Even Queen Caroline of Great Britain, who ruled at the end of the eighteenth century, was considered eccentric for taking baths. Washing clothes regularly was considered much more essential than washing yourself - clothes touched the body, people reasoned, so by washing them you were clean. Laundry was such a frequent task that women both free and enslaved would work in specific jobs as “washerwomen.”

Throughout the British colonies, being enslaved was synonymous with being a person of color. Race-based enslavement became an institution all its own in the American colonies, though this could include Blacks, Native Americans, or people of mixed race. Plantations were uncommon in New England, but most of the small-scale farming done in wealthy homes was carried out by enslaved people. In both the north and south, household labor was performed predominantly by enslaved workers.

Cooking was one of the major duties - enslaved people and servants were responsible for preparing meals, serving their white owners, and preparing large quantities of food for balls and galas. Spending hours over an open fire in an enclosed room, especially in the New England summer, would have been a suffocating experience for those tasked with cooking for the Shirley family. The kitchens at Shirley Place were in the basement for convenience to the Shirley family, who could be served faster and more conveniently. Despite the presence of a summer kitchen in the cooler northeast corner of the building, this was still a hardship for those they enslaved, who worked in the grueling summer heat.

Wooden washbasin, c. 19th century. The Shirley-Eustis House Association Collections, 2014WAT.092a. Image courtesy the author.

The final, and perhaps most notorious, form of household labor enslaved people carried out was childcare. The bounds of the family were blurred under the institution of slavery. Instead of being able to care for their own children, who were sold or given to other enslavers, enslaved women were expected to nurse white children who still held a form of power and ownership over them. Enslaved children were also frequently raised alongside their enslavers’ children, acting as both friends and property.

“New World slavery violated the basic human right to bear children and raise them. Children could be bought and sold away from parents. Other slaves and agents of the estate cared for children separated from kin.”

Several tools in the Shirley-Eustis House collection allow us to illustrate how enslaved people carried out their work in the house. The first is a mortar and pestle, pictured above, which would have been used to grind ingredients like herbs and spices into fine powders to use in cooking. Also in the media section are images of a laundry basin, washboard, and food chopper. Everything would have been done by hand - no convenient washing machines, microwaves, or mixers to be found.

Some Things Change: Differences Between Slavery in the Colonial South and New England

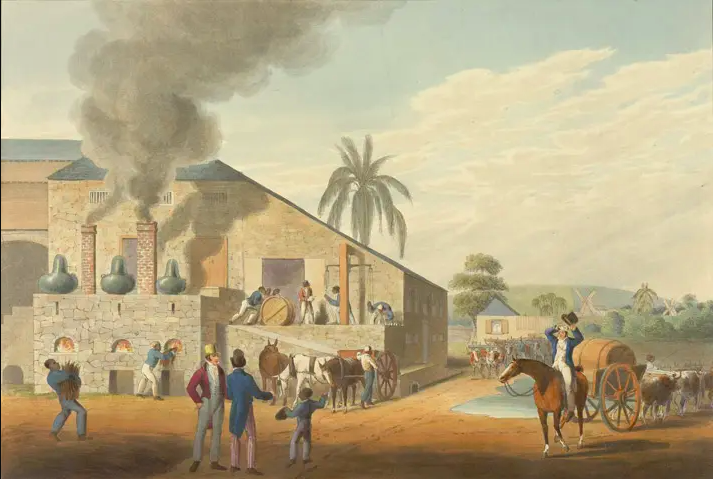

Exterior of the Curing House and Stills, Antigua, William Clark (c.1823). Photo courtesy The British Library.

Skilled vs. Unskilled Labor

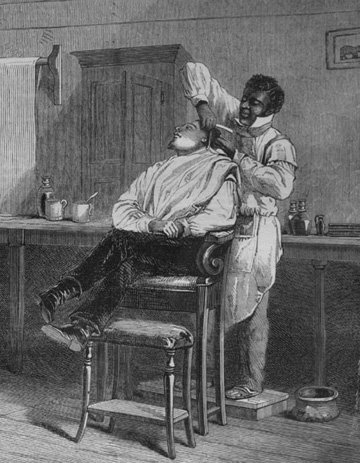

The distinction between “skilled” and “unskilled” labor is still a debate today. When it comes to enslavement, “skilled” labor generally refers to those who were trained and performed a trade. Those trades could include blacksmiths, fishing, cobblers, distillers, coopers, or more. “Unskilled” labor describes work done without any special training, like serving food, washing, or fieldwork.

Differentiating between “skilled” and “unskilled” labor carries with it quite a few problems. What types of labor are considered skilled? Which ones are unskilled? Why?

“Skilled” labor was usually only permitted to be performed by men. It was kinds of labor that either white or Black men could perform and usually labor that required several years of specific training. In New England, knowing a form of skilled labor was extremely valuable for an enslaved person. Enslavers who were able to sell their slaves’ labor or goods could make additional income without having to pay the person they enslaved. It was a lucrative deal for enslavers, as it was also one less specialized service for which they’d have to pay.

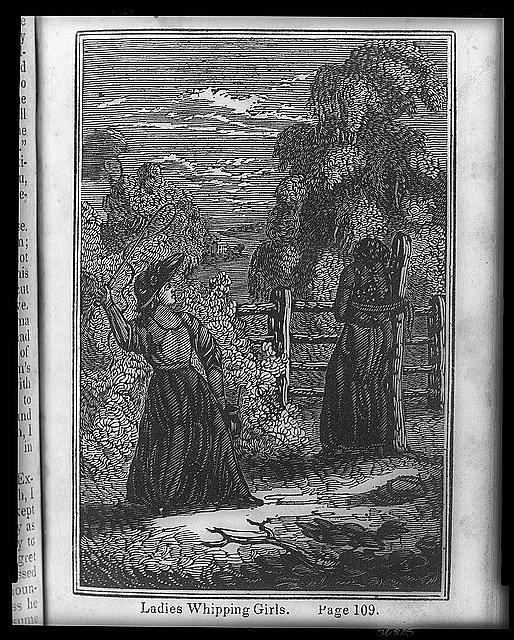

“Unskilled” labor, by contrast, is an inaccurate name. Tasks considered unskilled were primarily performed by women: nursing, childcare, cooking, cleaning, and laundry. Some were both male and female tasks, such as farming or fieldwork. However, it is a misconception that these jobs required no training. While they did not require the years of apprenticeship that trades did, they were still performed by enslaved women who had to know the most efficient and effective ways to carry them out. Learning the ins and outs of these roles took a lifetime. Cooking in a way that one’s enslaver did not like, for instance, carried with it the risk of punishment. Cleaning laundry incompletely could also bring about heavy consequences, as could failing to nurse a child, or leaving water stains on a wine glass. Though enslaved women were often called “unskilled laborers,” their work carried as much if not more consequences for them. Failing at a daily task an enslaver considered “easy” left women more vulnerable to punishment and to the unpredictability of their enslavers’ moods.

“Ladies Whipping Girls.” Illustration in George Bourne’s Pictures of Slavery in the United States of America (Middletown, CT: E. Hunt, 1834), p. 109.

There are several major differences between slavery in the colonial English south and New England. The first is that field labor was much less common in New England. Large farms were not part of the cultural landscape, and the long winter season was not conducive to growing cash crops like tobacco, rice, sugar, or indigo that thrived in southern colonies. While enslaved people still labored on smaller farms and outdoors, a household centered around economic life and indoor labor tended to require a much smaller staff than a hundred acre plantation whose head of household categorized himself as a “gentleman farmer.”

Enslavement in the northeast relied just as heavily on plantation farming as the southern colonies did, but in a different way. It was the crops produced by enslaved people that the northern colonies needed – into the 1800s, this mostly meant sugar and rum. The manufacturing economy of New England thrived on the low prices of raw sugar and molasses that southern plantations facilitated, and enslaved tradesmen and workers often produced the rum and refined sugar for which New England became famous. Enslaved people and indentured servants in the northeast also produced other goods that would be used in the transatlantic slave trade and supported the lifestyle of wealthy merchants who made their fortunes in human slavery and the secondary commerce it supported.

“A Barber’s Shop at Richmond, VA,” Eyre Crowe, The Illustrated London News, March 9, 1861. Detail. Image courtesy Wellcome Images.

The Lifelong Toll

Whether an enslaved person worked in the colonial English north or south, they were still enslaved. There is no such thing as “easy” versus “hard” slavery. Slavery is inherently dehumanizing. Enslaved people who worked in the fields on Virginia plantations had just as many rights as those who cooked in the Shirley household’s kitchen: none.

While one form of work may have been more strenuous than another, there were far more commonalities between enslaved people than differences. They were constantly at risk of losing their loved ones, their sense of culture, and what little peronal autonomy they might enjoy at the whim of their owners. They had hardly any time or privacy for themselves. There was no room for their own preferences or desires under the institution of slavery, and no space free from the influence of their enslaver or others like him. It is remarkable, given these deplorable conditions, that anyone, under any form of this system, managed to express discontent, survive, and seek their own freedom.