Enslaved Lives in the Shirley Household

< Back to Enslavement at Shirley Place

Enslavement in the Landscape

Architecture and landscape can reveal the impact of slavery, if you know where and how to look. At the Shirley Eustis House, four distinct places allow us to tell various stories of enslavement: the approach to the house, the kitchen, bedrooms, and a neighboring structure at 42-44 Shirley St.

The Shirley-Eustis House in Roxbury, MA. Photo courtesy the Shirley-Eustis House Association.

The answer is geometry. While the grand entries for upper-class visitors were in the east and west facades of the house, entryways for servants and enslaved people were on the north and south. This simple trick ensured that the upper and lower classes never intersected while entering the home. Servants and enslaved people could enter immediately into the kitchen and service area on the basement floor, while the Shirley family and their guests went immediately up the regal stairs and waited to be served.

The Approach

“The approach” is the view seen in the picture to the right. The mansion was built in 1747, and was the nerve center for activity on the Shirleys’ country estate - business, property management, and service would have all been conducted mostly in the mansion.

On the outside of the building, there are two floors and a basement - or are there? The front steps lead upward into what is the second floor, going up and over the first floor. This staircase and massive solid wood front door would have been reserved for elite guests invited to Shirley Place to make a grand entrance. They would have been welcomed in by a servant or enslaved person who was dressed in the Governor’s livery, ensuring that the guests knew they were in the presence of someone who represented the English empire. That would have been the only interaction the wealthy had directly and purposefully with servants or enslaved people in the house. So how did the house function, then, if those who ran it were supposed to remain invisible?

At right: This 1820 image of the Shirley-Eustis House shows a view of both the front and side entrances. While porches had been added onto the sides, there are still two distinct paths of entry to the house where the upper and lower classes would not have to intersect. Image courtesy the Shirley-Eustis House Association.

In addition to the practical impact of the house’s design, it also served as a symbol of Britain’s reach into the Americas. In fact, the house could, in the eighteenth century, be seen from Boston harbor. Its sizable cupola and giant Palladian window were the grandest features on any house in the surrounding area that person sailing into Boston would see. Shirley Place was very well known as the governor’s home, and considered a fine example of Palladian design in America. Today we know this as the “Georgian” style. The most distinctive Palladian features on the exterior of the Shirley-Eustis House are the pilaster columns on the (now) front entrance, the grand windows on the back entrance, and the house’s symmetry. These features projected British power clearly onto the landscape of Boston and would have symbolized the power the Shirley family held over those they enslaved just as clearly.

The Kitchen

The Shirley-Eustis House’s kitchens were located on the basement level. Unfortunately, the original Shirley Place kitchen has been lost to time, but we can use what we know about other kitchens in colonial New England homes to uncover the role enslaved people played in that part of the house.

The restored “winter kitchen” at the Royall House and Slave Quarters in Somerville, Massachusetts. This kitchen was originally constructed, along with the house, in 1690, but was renovated after Isaac Royall, Sr. purchased the land on which it was situated in 1737. Photo courtesy the Royall House and Slave Quarters.

Colonial kitchens centered on the hearth - all cooking was done over this open fire. Since cooking was so labor-intensive, the major meal of the day, what we might call dinner or supper, took place in mid-afternoon. The lighter fare was eaten for breakfast and in the evenings.

Several kitchen and household tools are found in the Shirley-Eustis House’s collections. From left to right: toasting fork, bread peel, butter paddle, wooden ladle, and laundry spoon. Photo taken by the author.

At the Shirley-Eustis House, the kitchen was not a separate building but operated below the family’s living quarters. It would have been run by enslaved or servant workers. It is likely that any enslaved people whose primary duties were to cook or serve the family would have slept in the kitchen, on the floor on straw-stuffed pillows and bedrolls to pad the rough ground. This would have allowed them to tend the kitchen fire overnight - it was much easier to keep the fire from going out than it was to restart it in the mornings.

While we do not have the remains of the Shirley-Eustis House kitchen, we know that people enslaved by the Shirley family would have used it nearly constantly to maintain the lavish lifestyle the family was used to. The social events held by the governor in his Roxbury mansion would have eclipsed almost anything else seen in Boston, and they were supported, ultimately, by enslaved people who carried out the labor which made them possible.

The Bedrooms

While the colonial American south typically used separate slave quarters to house enslaved people on expansive plantations, those structures were less common in New England. The Royall House and Slave Quarters is now home to the only surviving purpose-built slave quarters in New England. The Shirley-Eustis House employed only about five enslaved people compared to the Royall House’s approximately sixty, meaning that it would have been unusual to build an entire structure to house those individuals. Instead, most of the enslaved people at Shirley Place would have slept in the same bedrooms as their enslavers.

Since those enslaved by Governor Shirley completed primarily domestic duties, it would have been their responsibility to wake earlier than the family, light fires, cook breakfast, and prepare for the day. They also would have been called upon at all hours of the night to serve the Shirleys. As Edward Baptist outlined in his book The Half Has Never Been Told: Slavery and the Making of American Capitalism, “sleep…was broken” for the enslaved. For these reasons, at least a few of them would have slept in the quarters of the Shirleys. Not in a bed, of course, but on the floor or a pallet close enough that they could be called easily and woken quickly. In contrast to the enslavers, those enslaved were never able to rest, and never given a private space to call their own. It also means that the bedrooms in colonial homes that have been interpreted as bedrooms for white inhabitants were typically, instead, a shared space.

Re-centering the experience of enslaved people gives us an opportunity to consider the communal nature of colonial bedrooms in wealthy homes. They were not an exclusively white space, nor could they be if the house functioned in the way it was designed under the preexisting system. For those who were enslaved, bedrooms were inherently linked to work rather than sleep. Could enslaved people ever truly rest? Was there any space that allowed them to shed the label of “enslaved”?

This fully furnished reproduction of a Georgian-era bedroom is from The Georgian House in Edinburgh, Scotland. Photo courtesy Carly Brown on carlyjbrown.com.

42-44 Shirley Street

This building was originally part of the Shirley estate, but its purpose was unclear for quite some time. For many years staff theorized that it could have been a barn. It was possible it contained livestock in the ground floor and bedding for enslaved farm workers in the loft. This also could have been a space where those enslaved by the Shirley extended family slept when they were brought over.

Over the years, local residents passed down rumors that the building might have been a separate slave quarters, much like the building at the Isaac Royall House and Slave Quarters in Medford. That would have been a remarkable discovery but did not match what locals knew about the number of people Shirley’s family enslaved. Slave quarters likely would not have been built if a family only had five to six enslaved people – they would have slept and worked in the bedrooms and kitchen, more integrated with the white inhabitants.

The building at 42-44 Shirley Street today. It sits across the street from the Shirley-Eustis House Mansion. Photo courtesy The Shirley-Eustis House Association.

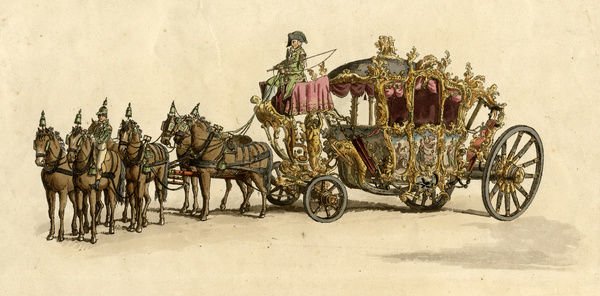

Upon closer inspection, The Boston Landmark Commission finally uncovered the building’s true purpose in 2022: a massive Georgian stable. Based on markings on the eighteenth century wooden beams, half of the building had been torn down at some point in time. When it was whole, in Shirley’s day, it was home to his many horses. They served as transportation and pulled the Governor’s impressive carriage – it was important that Shirley’s carriage reflect royalty in North America since the King himself was not present. The building also would have housed enslaved people whose duties involved working with the horses, handling Shirley’s livery, and serving as his footmen. Footmen would have run alongside the carriage as Shirley rode and helped him in the event he needed to disembark or serviced his needs at their destination.

Such an unassuming building, though owned by a private individual today, is an integral part of the story of enslavement at the Shirley-Eustis House. It reflects both Shirley’s support of the British Empire and the many enslaved people who were forced to work toward the goal of that empire’s expansion. It may have even been the closest thing to a private space some of the enslaved people at the Shirley-Eustis House experienced.

“Lord Mayor’s Show,” Unknown artist, 1805. Shirley would have had a similarly extravagant “coach and six,” which is why he needed a large stable at his summer home. Image courtesy the London Picture Archive.

In upper-class homes throughout the English colonies, the kitchen was a space separate from the main living quarters. The Shirleys were so wealthy that it was rare that they ever would have even set foot in the kitchen. Their servants—free and enslaved—did all the cooking and serving. Some homes, primarily in the colonial American south, had “summer kitchens” in separate buildings exterior to the main home on the estate. This prevented the family’s living quarters from getting too hot in the warm months, and provided a separate space for enslaved people to sleep, typically in the attic of the summer kitchen.