Enslaved Lives in the Shirley Household

< Back to Enslavement in New England

Slavery vs Servitude

Distinctions in Definitions

There are two primary forms of labor that characterized English colonial societies: enslavement and servitude. Enslavement is the focus of this exhibit and describes when one person purchases another, eliminating their personal rights and treating them as a piece of property. Servitude is the payment of a person for services or work carried out for another person. While servitude is characterized by lower-class members of society, enslavement became, starting in the eighteenth century, characterized by race. Servitude could include whites as well as people of color, but it always referred to people who retained some level of personal and human rights. Their labor, rather than their bodies and personhood, was the object for sale.

The Kitchen Maid, Jean Siméon Chardin, 1738. Image courtesy the National Gallery of Art.

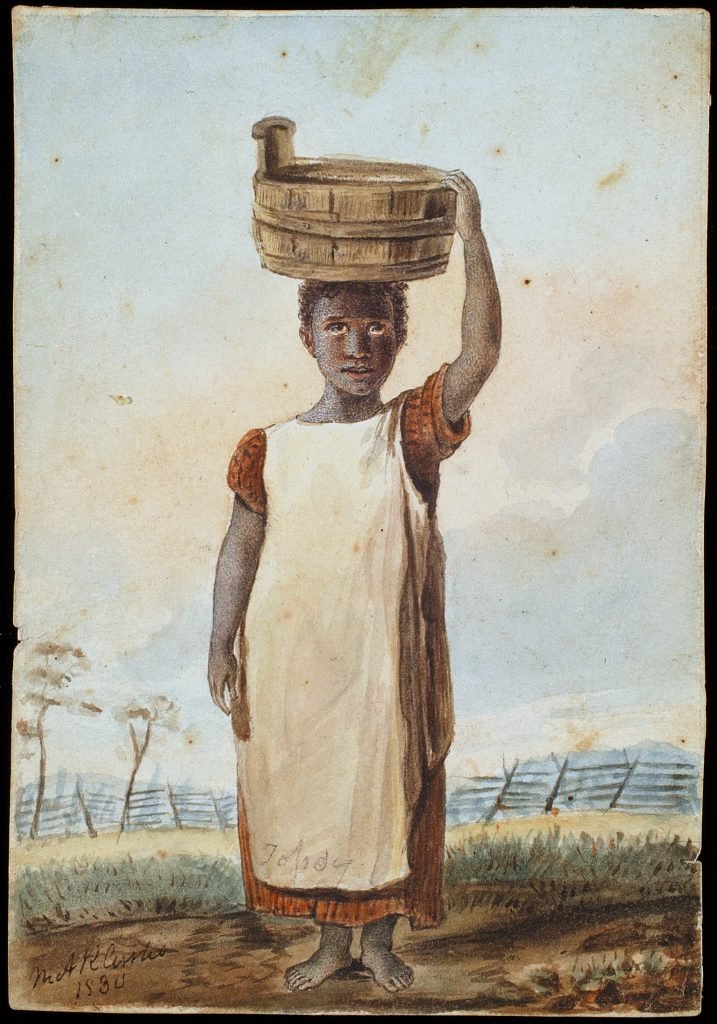

Enslaved Girl, Mary Randolph Custis Lee, 1830. Image courtesy the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Servitude includes another specific category of labor within its definition: indentures. Indentured servants existed somewhere between the enslaved and servants. Indentured servants were usually poor whites who signed a contract (or whose parents signed a contract) granting them room, board, and possibly apprenticeship in exchange for performing labor for a certain period. In the early colonial era, indentured servants often traveled to the English colonies with the family they served in exchange for the indenture’s labor. While this meant that the indentured servant was bound to the person they served, they entered the agreement with the expectation that they would complete their contract and move on with their life once its terms were up. Indentured servitude was unlike slavery in two important ways: it was not predetermined by birth, and it was not lifelong. Still, indentured servitude showed just how expendable the lower classes were to the British elite; whether these lower classes were Black or white. Note that in the contract pictured below, the indentured man, Henry Mayer, signed his name with an “X" - meaning he was illiterate.

At left: Indenture contract between Henry Mayer, the indentured, and Abraham Hestant, the indenturer, from Bucks County, Pennsylvania. This contract dates back to 1738. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Of course, there were certainly people who came to the North American colonies and carried out labor for themselves and their families without the use of enslaved people or servants. This was rare, however. Among people who did not employ additional labor, it was common that they were too poor to pay for it. As a result, they strove to eventually become successful and buy or pay their own laborers. Having servants, and especially slaves, was a mark of high status.

Unequal Footing

White and Black laborers often worked together in Boston, even though their societies still maintained intense segregation from one another. If enslaved labor was used, the enslaver would generally be paid for services rather than the enslaved worker, while white workers earned their own wages. Even free Black workers were usually paid less than white workers who carried out the exact same tasks.

Benjamin Eustis’ Account Book, Dr. Benjamin Eustis, 1750. At the top of this page, Eustis has charged Eliakim Hutchinson, William Shirley’s son-in-law, meaning that the three knew each other at least relatively well. Image courtesy the author.

The Role of Race

The most important factor distinguishing enslaved people from servants was race. While free Blacks and Native Americans could work as servants, getting paid for their labor, white people were never enslaved in the English colonies. Ibram Kendi’s book Stamped from the Beginning is a detailed chronicle of how African people came to be the sole group that was enslaved in North America. To summarize, “...racist ideas were nearly two centuries old when Puritans used them in the 1630s to legalize and codify New England slavery – and Virginians had done the same in the 1620s.” These racist reasonings varied between the theory that Africans were naturally disposed to farm work, that God had cursed their ancestors to serve white Europeans, or that they were more developmentally like animals than humans.

Racism in some form has existed throughout much of human history, as has enslavement. The marriage of these two ideas to become enslavement based on one’s race is a new invention in the last five hundred years. In North America generally, the status of freedom or enslavement passed to children through their mother – if she was free, they were free. Free Black communities thrived throughout the English colonies, but they still faced economically and socially crippling racism and the fear that they would one day be thrust back into enslavement. Slavery was a constant threat to Black people and communities, regardless of whether they themselves were free or enslaved.

One of the builders who worked on the construction of the Shirley-Eustis House in 1747, Benjamin Eustis, often relied on the labor of an enslaved man named William. In Eustis’ journal, he lists the amount paid to various workers he employed on different projects. While he did in fact pay William for his labor, he paid him half the amount white men were paid for the same amount of time and work.

Two theories for this are possible. First, William was enslaved by Eustis. In his journal, Eustis often refers to William as “my boy” or “my lad.” It is possible, though unlikely, that Eustis would have paid him for his labor. Eustis recorded the value of his own personal labor throughout his ledger, so it is more likely that if he enslaved William, he was simply recording the cost of his labor on projects. Second, William could have been enslaved by someone else and only employed by Eustis for specific projects. If this were the case, Eustis would have paid William’s enslaver for the man’s labor. Unfortunately, like with many enslaved people in the eighteenth century, William’s story remains incomplete for us today. While we can theorize about what likely happened, we do not know for sure.