Enslaved Lives in the Shirley Household

The British Slave Trade in Shirley’s Day

It is estimated that in the 1730s alone, British ships carried 170,000 enslaved people on their trade routes to places including the Caribbean, the North American colonies, and Britain itself. To help you visualize that number, here are some comparisons:

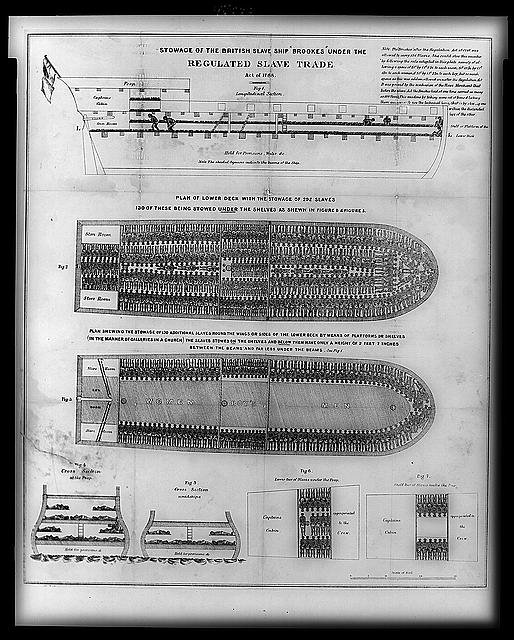

Stowage of the British vessel “Brookes,” which was loaded with enslaved people under the “Regulated Slave Trade Act” of 1788. This act limited the number of enslaved people allowed as cargo on a single ship based on the ship’s size and berth. It was the first British law passed to regulate the slave trade. Many ships ignored it.

Boston’s total population in 1770 was about 15,000 people.

The present-day population of Providence, Rhode Island is 179,494 people.

In about twelve hours, some 192,000 babies are born around the world.

The eighteenth century was a peak for the British slave trade. As we have already established, its colonial foothold in North America required enslaved labor to function and provide the Motherland with the natural resources found across the Atlantic. After the European race for power in the early 1700s, Britain became much more confident and robust in its trade of African lives for the rest of the eighteenth century.

Global Trade Networks

The slave trade was one dark side of the increasing global connections that were formed through trade in the eighteenth century. Corridors opened from Europe to Asia, India, Africa, and the Americas. The work of enslaved people facilitated this trade, as it was the sugar, rice, tobacco, indigo, and other crops on American and Caribbean plantations that the British were using as commodities.

Owning plantations and enslaved people came to represent wealth and power for British elites. Enslaved Africans were often compared in British sources to livestock, so a large staff of enslaved workers meant that one had the means to purchase and operate an expansive estate. Those deeply involved in the slave trade used their wealth on other purchases, as well. Many merchants based in New England built luxurious homes much like Shirley Place with the money they made – though we are not sure whether Shirley himself ever traded in human lives on a large scale. Some slave traders used their revenue to start other businesses, like manufacturing, mining, and architecture. Others invested their money into art and sculpture. World-renowned universities such as Harvard, Yale, and Georgetown were founded with enslaved labor and revenue, then named for enslavers. No industry was safe from contamination.

“Elihu Yale with Members of His Family and an Enslaved Child,” ca. 1719, attributed to John Verelst. Detail. Image courtesy the Yale Center for British Art.

Growing Resistance

As more and more enslaved Africans were brought to Europe and the Americas, and as new generations of enslaved people who spoke a common language were born, it became easier for those enslaved to organize. In New England, enslaved people were generally encouraged to attend worship services with their enslavers. In the south, large plantations enabled enslaved people to interact daily and form connections with one another. Britain’s Black population (enslaved and free) reached 15,000 in the late eighteenth century. Most were concentrated in a few major port cities.

Resistance could take many forms across the Empire. There were violent uprisings such as the Stono Rebellion, in which twenty enslaved men fought against their enslavers near Charleston in the Carolina colony. These efforts ended in death on both sides and harsh punishments for any enslaved people who participated. Ideas of rebellion were incredibly dangerous for enslaved Africans to be caught disseminating or even just saying aloud. Similarly dangerous was running away from an enslaver. If an enslaved person was captured after running away, they would most often be tortured, beaten, or killed. This remained a very popular form of resistance, however, as is evident from the large number of runaway slave advertisements placed all over the British Empire.

At right: This wagon jack would have been used by enslaved people or servants to support a wagon while fixing a broken wheel. If enslaved people wanted to show resistance toward their enslavers, they might break wheels on wagons so that increased time and money were spent fixing them. Breaking a wagon wheel would halt work or trade until the wheel was fixed. Image via the author.

There were safer forms of resistance, too, though they were still not without risk. One was to slow work on the plantation or in the household. The institution of enslavement thrived on productivity, so purposefully not doing jobs correctly could prevent the enslaver from making money for a period. Keeping African culture and community alive through song and art could also be considered a form of resistance. Slavery meant to eliminate the idea that the enslaved were humans like their enslavers – anything that kept humanity alive, then, could be considered effective resistance.