Wealthy new englanders’ roles

While we address enslavement in New England in a separate section of the exhibit, it is important to highlight how New Englanders actively supported the global slave trade, as well. Working-class white New Englanders did enslave people, but not to the scale wealthy residents were able to. It was their money that helped fund the slave trade, especially for Britain.

Dependence on the global economy

Aside from just enslaving people directly, New England depended on enslaved labor in other parts of the world to support its own manufacturing and trade-based economy. The plantations in the southern colonies and Caribbean produced sugar, tobacco, and cotton. Merchants in Boston traded Africans for other goods, even if they never saw them in person.

“View of Faneuil Hall in Boston, Massachusetts,” March 1789. Samuel Hill, engraver. Image courtesy the Library of Congress.

Peter Faneuil is the most infamous example of a New England merchant whose dealings in the slave trade have tarnished his legacy. He constructed Faneuil Hall, a marketplace and public meeting space, in 1742 as a gift to the city of Boston. The National Park Service, which owns and cares for the space today, writes that “Faneuil himself owned enslaved people of African descent in his household, traded extensively in goods produced by enslaved labor, supplied materials that supported plantation economies, and his capital directly funded several voyages to purchase enslaved Africans off the coast of Sierra Leone.” One of the most famous spaces in the city of Boston was thus underwritten by enslaved labor.

Similarly, one of the most elegant eighteenth-century homes in Rhode Island, owned by merchant John Brown, was financed directly by the slave trade. Brown’s father facilitated the first slave ship launch from the port in Providence in the 1730s, the same time William Shirley was rising to prominence about fifty miles north. Providence would become one of the busiest ports for the British slave trade in the northeast. Eventually, Brown’s ships were confiscated because he violated laws against the importation of enslaved Africans. But this was long after his business had torn hundreds of families apart and likely thousands of Africans from their homes.

the shirley family

We do not know whether Shirley’s mercantile trading was supported by the enslaving and transport of Africans. It is possible that he could have made money in the slave trade without even knowing, or with his full knowledge and awareness. He could have done business with an enslaver – this was incredibly likely in a society where many of the upper class was involved in that economy. While Royal Governor of the Bahamas, Shirley was gifted at least one enslaved person by a wealthy British merchant.

Shirley showed his implicit support for the slave trade through one of the most impactful pieces of legislation passed during his tenure. In 1754, Shirley signed a law mandating a tax on enslaved people owned in Massachusetts. Likely done to increase the colony’s (and therefore the British empire’s) revenue, the law was not liked among the wealthy. It became common for wealthy families to sell or lend enslaved people to others to circumvent the taxation. However, Shirley was a man of the empire before he was an individual. In both roles, he was an enslaver.

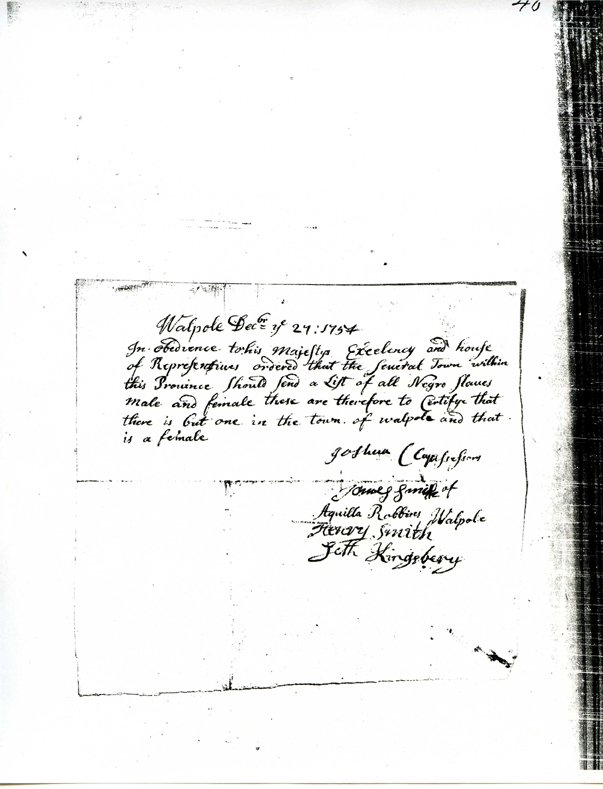

This document was written in response to the census of enslaved persons passed in 1754, during Shirley’s tenure as Governor of Massachusetts. In it, the Walpole town council signs off on the count of enslaved people in the town of Walpole: one female. It is unclear whether their census was accurate. Image courtesy PrimaryResearch.org.

Shirley’s family was a part of the slave trade, as well. His daughter Elizabeth married Eliakim Hutchinson, and the couple would eventually own more enslaved individuals than Shirley ever did. So did his daughter Harriet and her husband, Robert Temple, Jr. Shirley also served as the Governor of the Bahamas after his tenure in Massachusetts, where he likely would have witnessed the horrors of slavery on plantations much more closely than he had in Massachusetts Bay.