Name that War! Part 3

By Bill Kuttner

Editor’s note: In his December blog entry, Bill Kuttner looked at the impact of 17th century European wars on the process of colonization in North America. In this post, we learn how later European conflicts spilled over into colonial territories, enveloped indigenous populations and seemed only to lead to more warfare.

Dynastic Wars and Colonial Power

While religion did not disappear as an issue, the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 ending the Thirty Years’ War is often considered the close of Europe’s Wars of Religion. But with the new economic doctrine of mercantilism, the race to control resources and markets in foreign lands intensified, leading inevitably to conflict. Not surprisingly, wars continued in Europe, some financed with gold and silver from Mexico and Peru.

These were also the first world-wide conflicts with the mobilization of colonial forces. Issues of world trade and colonial possessions now would need to be addressed, if not necessarily resolved, in the peace negotiations.

While European states might challenge the Ottoman, Aztec, or Mughal Empires whenever the time seemed opportune, conflict between the Christian states in Europe were expected to have some sort of pretext. Any ambiguity in the line of succession in a kingdom, duchy, county, or bishopric might spark military action by one party. Many European powers would choose sides in different combinations as their interests dictated.

In these “Dynastic Wars”, Britain was always on the side opposing the continental superpower, France. Britain’s “balance of power” policy sought to prevent the rise of a continental hegemon and would continue as other continental powers later surpassed France

The boundaries of the contested European territories had been established centuries earlier in the Middle Ages, and once the succession question was settled, most boundaries reverted to the status quo ante. But overseas claims were vaguely defined and in a state of flux. It was still the age of exploration when Spanish missionaries might encounter Russian seal hunters in northern California at the extremities of their imperial dominions. Boundaries might be non-existent, poorly mapped, or ignored, and explorers often did not know where precisely they were.

There were four major dynastic wars significant in American history, and the North American theaters of these wars had their own names. The participants in America also had their own motivations for fighting, and the issues of the North American conflict were addressed in the peace negotiations that ended the dynastic war.

This essay summarizes presents the first three dynastic conflicts and their three associated North American wars. The thesis of this series is that struggles in Europe had important implications for the colonies. By the end of this episode, the colonies are beginning to influence European history. Massachusetts Royal Governor William Shirley emerges as an important figure at the end of this installment and will be joined by young Colonel Washington early in the next.

The pomp and ceremony of European treaty negotiations such as those for the Treaty of Ryswik in 1697, were far removed from the colonies they affected. Months after the treaties were signed and diplomats and their entourages had returned home, colonial subjects received a small pamphlet with the Treaty's terms, which might by then be already out of date.

War of the League of Augsburg, 1689-1697

Charles the II, the unimpressive Elector of the Rhineland-Palatinate died without issue. His brother-in-law, Louis XIV of France, claimed ownership of most of the territories. William of Orange, Stadholder of the Dutch Republic, persuaded Austria, Sweden, Spain, Savoy, and the electors of Bavaria and Saxony to join together to resist Louis. The many new Protestant Huguenot citizens in these lands, recently exiled from France, cheered this move.

In 1689 Parliament invited William of Orange to replace his father-in-law, James II, as King of England. With the addition of British forces, the League acted and after eight years of fighting, Louis gave up his Palatinate claim at the Treaty of Ryswick. France was, however, given Haiti from Spain.

King William’s War

Massachusetts Royal Governor, Sir William Phips, led colonial forces that captured Port Royal, Nova Scotia, today’s Annapolis Royal. A subsequent assault on Quebec failed. The Treaty of Ryswick restored Port Royal to France.

Aside from the Iroquois, most northeastern tribes backed France. Notable massacres included Schenectady and Casco Bay. A former privateer, Phips is best remembered in Massachusetts for ending the Salem witch trials.

War of Spanish Succession, 1701-1714

When King Charles II of Spain died without issue in 1700 Louis XIV claimed the throne for his grandson, crowned as Philip V. Charles agreed in his dying wish. This violated an understanding with Britain and the Dutch Republic that France and Spain would never be united under Bourbon rule.

Again, a dozen European states chose sides. John Churchill, the Duke of Marlborough, led the allies’ largely successful campaigns. Gibraltar [gateway to valuable Mediterranean trading ports] was captured. Philip remained King of Spain, but union with France was forbidden.

Queen Anne’s War

French, Abenaki and Pocumtic fighters from Canada raided Deerfield in 1704. Then Port Royal was captured by New England colonial forces again. The Treaty of Utrech(1713) recognized Britain’s claim to Newfoundland, Hudson’s Bay, and a loosely defined “Acadia,” which included mainland Nova Scotia and the Maine seacoast. Port Royal was renamed Annapolis Royal. France retained Cape Breton Island and (today’s) Prince Edward Island. Soon thereafter construction began on the Louisburg fortress, which would play such a big role in Governor Shirley’s career.

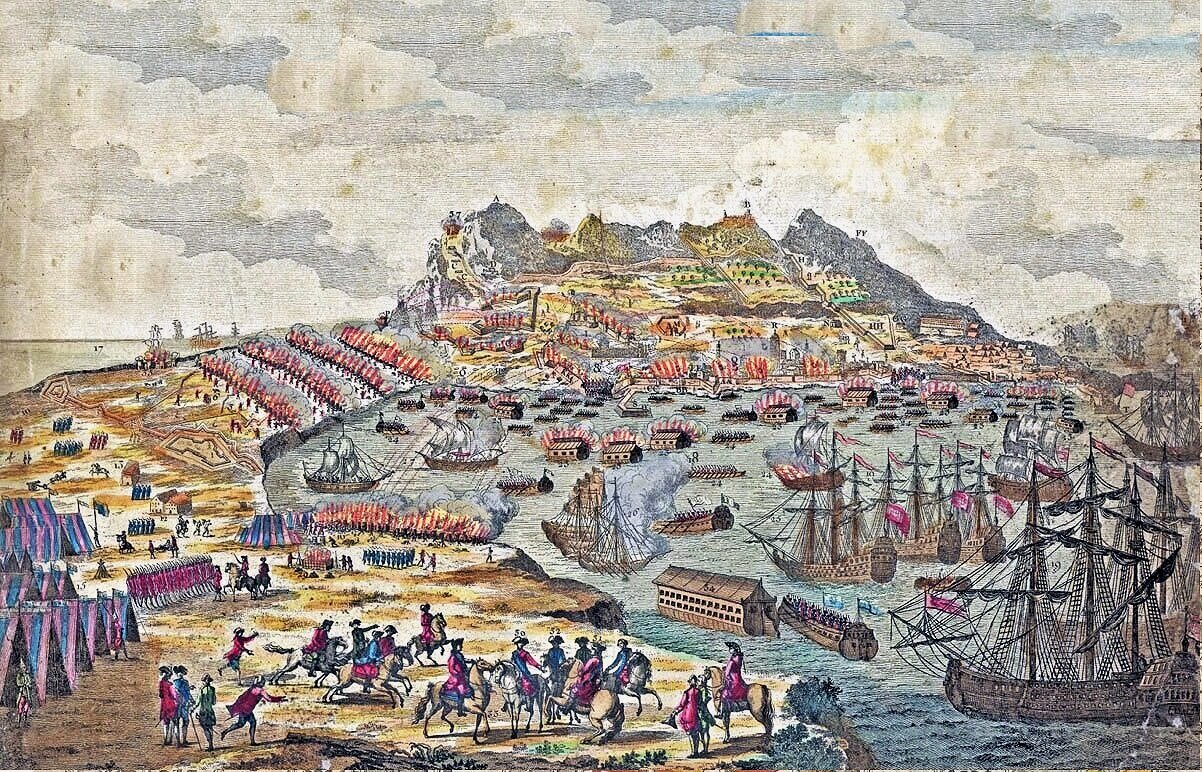

The British Assault on Gibraltar, Spain, a vital control point for the Mediterranean trade routes. British warships bearing their red flags enter the harbor from the right, while lines of troops assault the rock from the left

War of Austrian Succession, 1740-1748

The Holy Roman Emperor, Charles VI, had no male heir. He ruled over many lands with ancient laws. Some allowed rule by a woman; others did not. Charles requested that the European Sovereigns recognize his eldest daughter, Archduchess Maria Theresa, as Queen in lands such as Hungary, and Regent in the other lands for an as yet unborn male heir. Shortly after Charles’ death, the Elector of Bavaria, backed by France, asserted his own claim. European states chose sides.

In a dynastic war-within-a-war, France financed the rising of the Scottish clans under Bonnie Prince Charlie, grandson of the deposed James II, in the Second Jacobite Rebellion. British forces under the Duke of Cumberland, the son of King George II, unsuccessful against the French in Flanders, returned to Britain to face this threat. Cumberland eventually crushed the rebellion at Culloden Moor, infamous for the killing of wounded highlanders.

King George’s War

A notable and unexpected British success was the capture of Louisburg in Nova Scotia by New England forces organized by Massachusetts Royal Governor William Shirley. Negotiating in Aix-la-Chappelle (modern-day Aachen) from a position of weakness, Britain later returned Louisburg to France in exchange for commercially valuable Madras in India. Composer George Frideric Handel celebrated the peace treaty with the Music for the Royal Fireworks (listen here: youtube.com/watch?v=qHTu91hplhE) .

Archduchess Maria Theresa was a formidable figure in the world of absolutist monarchs. She ruled over Austria, Hungary, Croatian, Bohemia, Transylvania, parts of Northern Italy and the Austrian Netherlands from 1740 until 1780. While pursuing reforms in education, medicine, and finance that benefitted her subjects she aggressively quelled religious dissent. All this while giving birth to sixteen children and surviving smallpox.

Marie Antoinette and the “Diplomatic Revolution”

Silesia was a prosperous, German-speaking duchy north of Bohemia, today part of Poland. After the duke died without issue in 1675, Silesia, part of the Holy Roman Empire, came to be ruled directly by the Hapsburg Emperor. The upstart power, neighboring Prussia, asserted that the grounds for Hapsburg rule were faulty.

While not technically allied with France, Prussia took advantage of Austria’s struggle to seize Silesia. Austria tried in the First and Second Silesian Wars, fought in the midst of the War of Austrian Succession, to recover Silesia. With ineffectual support from its British ally, Austrian forces were only able to secure Maria Theresa’s regency, but not Silesia itself.

Maria Theresa’s husband, Francis Stephen, was elected Holy Roman Emperor, and their family quickly expanded including the future emperor Joseph II (portrayed in the movie Amadeus) and his sister, Marie Antoinette. Austria was not ready to give up on its claim to Silesia and sounded out France on the potential of an alliance. France agreed, an event dubbed by contemporaries as the “Diplomatic Revolution.” Fourteen-year-old Marie Antoinette played her obligatory part by marrying the Dauphin of France, the future Louis XVI.

No One is Satisfied

Only the succession issues in Europe seemed to be resolved. Maria Theresa’s regency continued, and Britain’s young House of Hannover survived another Jacobite rebellion. Austria still planned to recover Silesia, and victorious Prussia was for the moment without allies. France did not have a recognized claim to North America’s great river system by which its colonies in Quebec and New Orleans could communicate and support each other. Meanwhile, America’s restless colonists looked to the continent’s interior and saw only opportunity. This is where the spark would ignite what would be the world’s first global conflict.

The British naval assault on Gibraltar, a vital control point for trade around the Mediterranean. The British ships, bearing red flags, bear down on the harbor from the right, while lines of troops make a land assault from the left.