Enslaved Lives in the Shirley Household

< Back to Enslavement in New England

Degrees of Unfreedom

“Daguerrotype of Caesar - A Slave,” 1851. Caesar was rumored to have been born in 1737 in Bethlehem, NY, making him one hundred and fourteen years old at the time of this daguerrotype. He was enslaved by the same family for his whole life, outliving them for at least three generations of enslavers.

Enslaved Children as “Gifts”

Enslaved children were treated much differently than enslaved adults. It was unusual for whites in New England to want enslaved children because they couldn’t work immediately and were even considered a liability when their parents had to care for them instead of working. “Black babies and children ‘to be given away’ were sometimes offered by the slaveowner with money or other things of value as an incentive for someone to take the baby,” writes Aabid Allibhai in his “Working Report on Slavery at Shirley Place.” Enslaved babies and young children were treated as something akin to a pet - enslavers found them entertaining, but not useful.

Throughout New England, some enslaved people had more individual freedom than others. Relationships between enslavers and enslaved certainly played a large role in the modest liberties a captive might enjoy – some enslavers were very open about their favorites. Enslaved people who were well-trusted tended to be allowed the freedom to travel off the estate or household (though certainly not very far), make business and personal decisions for the enslaver, and avoid punishment more easily. Thomas Scipio may have enjoyed this kind of relationship with William Shirley since he traveled with the Governor to England, and was in the household for many decades, even after the death of Shirley himself.

According to Joanne Pope Melish, author of Disowning Slavery: Gradual Emancipation and “Race” in New England, 1780-1860, about a third of all Black people in New England lived in Boston in 1754. This made it possible for enslaved people to develop deep networks of connection and community with other Black New Englanders more easily than enslaved people on isolated plantations in the south. While some enslavers discouraged these connections, many considered the people they enslaved to be like family in some form. This complicated the relationship between enslavers and the enslaved as family, property, or something in between.

It is a mistake to assume this meant some enslaved people had an “easy” life. The trust some enslaved people cultivated with their enslavers was fragile and depended heavily on the mood or temperament of those who enslaved them. Like many other actions under slavery, familiarity and friendliness with an enslaver were often strategies for survival.

“Lady Grace Carteret, Countess of Dysart with a Child and a Black Servant, Cockatoo, and Spaniel,” John Giles Eccardt, 1779. Detail.

However, as historian Jared Ross Hardesty writes, “Boston’s requirements were…quite different from those of other regions of the Americas, where bound laborers worked primarily in agriculture. The town had a sophisticated mercantile economy that depended upon skilled workers who could provide specialized services…” This meant that enslaved babies were also like an investment, at least for those who could afford to raise them. Once they were old enough to begin working, they could be trained in a trade or in housework. In the painting above, the so-called “Black Servant” is only a few years older than the white girl next to him, and is oddly positioned to make him a subject who also fades slightly into the background. Is he being treated as a person or a prop?

Cashing In: The Sale of Enslaved Labor

“A more complicated view acknowledges that slaves were unable fundamentally to alter their condition, recognizes that exploitation exacted real costs and engendered long term harm, and then explores the ability of slaves, often under the most difficult of circumstances, to influence the conditions of their lives and to exercise some control over their day-to-day existence.”

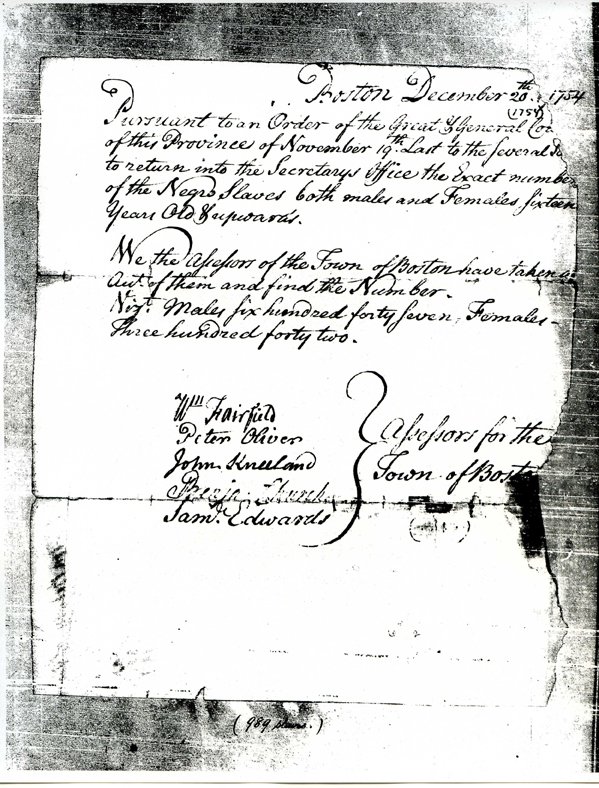

The matter of who “owned” an enslaved person was much more complicated in New England than in the southern colonies. Governor Shirley signed a bill in 1754 mandating that slave owners pay a tax to the colony on all those they enslaved. While he was most likely trying to increase the colony’s revenue, the bill was not as effective as he hoped. Enslavers now tried to minimize and downplay the number of enslaved people on their census so they could pay as few taxes as possible. When an enslaved person worked for multiple families, it was difficult to discern who enslaved them, and difficult for officials to prove who “owned” them based on where the enslaved person spent their time.

Letter reporting the results of the 1754 Slave Census in Massachusetts. This letter counts “Negro Slaves” in the town of Boston over the age of sixteen. It claims there were 647 men and 342 women. It is unclear whether this count was accurate. Image courtesy PrimaryResearch.org.

Many Blacks, both enslaved and free, constituted a well-sought after workforce in New England. The New England economy just before the American Revolution was bursting at the seams, and even for white men, it relied heavily on workers who would perform short-term projects rather than developing long-term careers. At times, enslavers would sell the labor of their own slaves to other people and reap the profits. It was an easy way for the upper class to make a profit – it required none of their own labor, and only that they adjust to a less productive household for a short period of time. At the Shirley-Eustis House, one of the mansion’s carpenters was known to rent enslaved people to work on his projects. Find his story in Slavery vs. Servitude.

In a few cases, even free Black New Englanders would hire the labor of enslaved people from their neighbors. Abijah Prince, who had formerly been enslaved, rented the labor of two men named Titus and Cato from a white enslaver named Jonathan Ashley. Prince employed the men in yard work and farm work for about three months, paying Ashley for their labor. The practice was so accepted in New England society that Prince, even though he was able to empathize with Titus and Cato’s situation, still turned to enslaved labor to support his own family. How do you think Prince felt about his decision?

City Gazette and Daily Advertiser, Charleston, August 1, 1791. This enslaved man had several incredibly valuable skills, including as a cooper, sailor, and cook. His enslaver would have considered those traits assets.

Enslaved people were also sometimes able to make money for their own labor. This level of freedom was rare but did happen. Often, this labor occurred after the main tasks for the day had been completed. Craftsmen and artisans were most in-demand and found it easiest to make extra income for their specialized labor. Farriers, carpenters, and seamstresses were among the most popular enslaved laborers since it took so long to learn their trades well. Since they could not charge as much as a free white artisan, their labor was extremely competitively priced for the middle and lower-class whites. Elizabeth Keckley, Mary Todd Lincoln’s seamstress in the 1860s, is a famous example of a woman who earned enough money through her own labor to buy her own freedom.

The sale of enslaved labor, whether by enslaved people themselves or their enslavers, allowed for both freedom and control. While some enslaved people were able to make an income, meet new people, and travel to new places, others were taken advantage of. They saw none of the fruits of their labor and may have been separated from their families. Even those who sold their own labor could have the profits taken away by their enslaver in an instant. There was a level of power granted, but it remained fragile.